|

What follows is a description of a recent vacation to California and western Nevada. Many

RyPN readers, being better traveled than myself, will find nothing new in this epistle, having been to the sites I visited many times, when lots more was going on there. For this home bound writer, however, it was finally a chance to actually see, with his own eyes, some historic places and things I had only been tantalized by in books, magazines and the movies for the last 50 years. Here, at last, was my chance to stand in the shoes of Lucius Beebe, Richard Steinheimer and the many other photographers whose images I had worshipped since childhood. So, changing tenses, here is another yearly report on "What I did on my summer (actually fall) vacation".

October is not the best time to be visiting tourist railroads and museums, as many have gone to weekend-only operation if they're open at all. When you're No. 201 on a seniority roster, however, you're glad to get two weeks together, not in February. We depart on a Wednesday, "Sunday" in my workweek, for Chicago and Sacramento. Check-in at the airport, supposedly a nightmare since 9-11, takes only an extra few minutes. I wonder what the complainers would do if faced with a real inconvenience. Leaving Chicago, a young child has an asthma attack, so we divert to Denver, where the family is removed. This is my first trip to the new Denver airport, but we stay aboard the plane and do not get to see the infamous machinery that ate everyone's baggage. They've talked about running light or heavy commuter rail out to this remote site for years, but nothing has happened yet. Leaving, there is a good view of the city and mountains, but I fail to spot Denver Union Station or the

Colorado Railroad Museum. I do see the Winter Park ski area, long the destination of the Rio Grande's ski train, and wonder if the now privately-operated venture will continue since principal Phillip Anschutz has been named as America's top corporate crook. It's good viewing all the way to California, but there is little narration of what we're seeing, perhaps as a courtesy to those stuck in the center or aisle seats. Other than Lake Tahoe, it's a nameless expanse of mountains and desert.

Picking up the rental car at Sacramento is a breeze. There are no small economy cars available, and though that's all we paid for, we're offered a Buick or van. We take a white Century and pretend to be doctors on vacation. We find our downtown motel, and explore the center city briefly on foot. Downtown Sacramento appears to have undergone a previous partial revitalization, that has taken a slight downturn. K Street is bricked over, closed to vehicular traffic, and plied by the twin tracks of the local light rail system. At the west end of the street is the Downtown Plaza shopping mall, which seems to have good business, but as you progress eastward toward downtown, there are more empty stores. The modern, articulated light rail vehicles are operated in long trains, and full at rush hour. There is no regular operation of historic trolleys over the route, though I seem to recall it did occur when the system first opened, with borrowed equipment. Most restaurants near the beautifully-landscaped capitol close at

5 PM, when the state workers depart, and the Greek fast food place we patronize isn't very good. Sacramento's homeless population is smaller than San Francisco's, and we encounter only one "excuse me sir" attempted panhandling.

A walk toward the Sacramento River brings us to the California State Railroad Museum

the next morning. We're a bit early, so we explored the adjacent Old Sacramento, the original part of the city. Old Sacramento was nearly demolished when the I-5 freeway was constructed in the 1960s. Preservationists rallied to save the city's oldest structures, and the roadway was diverted slightly from its planned riverside location to spare the historic site. A combination of 19th Century buildings (some as old as the 1850s) and new sympathetic construction now house the usual gift shops, restaurants and art galleries.

The old board sidewalks contrast sharply with the roar of the Interstate overhead. Parked in the Sacramento River is the sternwheeler

Delta King, twin of the Mississippi's Delta Queen. Both once plied this route, until the Queen was taken through the Panama Canal and resurrected on the Father of Waters as a tourist boat in the 1940s. The King, which last operated under steam about 1946, came close to destruction several times until it was converted to a floating hotel here. Though it looks relatively complete and original on the outside, its machinery and engines were removed for spares when the Queen moved east. The interior has been converted into a modern hotel and restaurant.

Promptly at 10 AM, we enter the museum with a group of enthusiastic first graders and meet Paul Hammond. In days gone by, Paul was my boss at

Locomotive & Railway Preservation magazine, having assumed the editor's position after

Pentrex purchased the periodical from creator Mark Smith. With the magazine's demise, Paul left the cold Wisconsin winters behind and returned to his native California. He is now Director of Marketing for the California State Railroad Museum Foundation, a paid position which guides activities of volunteers at the Museum.

|

|

|

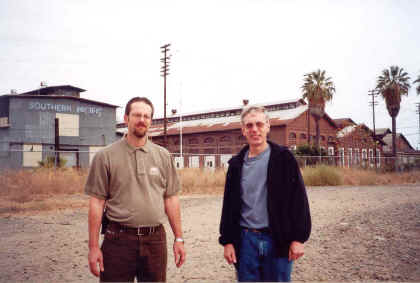

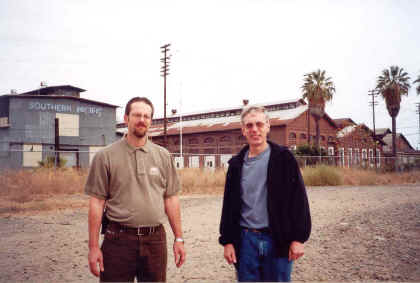

Left,

Paul Hammond, former Editor of Locomotive & Railway Preservation magazine and Bob Yarger, former News Editor of same, meet again six years after the magazine's demise. |

While most such organizations struggle to fund or accomplish anything, CSRM's Foundation (which is also involved at the Museum's

Railtown 1897 site in Jamestown) has the equivalent of 25-30 compensated full-time employees, in charge of roughly 700 active volunteers. In 2001, volunteers donated an incredible 107,000 hours of work. The Foundation is the principal organizer of Museum activities, does fundraising for restoration projects and is active in the state politics necessary to get things done. Volunteers have assumed a large percentage of the Museum's staffing. Some even ride Amtrak's California Zephyr daily between Sacramento and Reno, providing narration of sights and history along the route.

|

|

|

Entering the Museum, one first sees this 19-inch gauge 4-6-2, one of four built to haul visitors at the 1915 Pan Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. No. 1915 was never fully completed, though the other three operate today on a ranch at Swanton, California. |

The museum itself, housed in a modern building with a roundhouse-like fašade on one corner, is clean and

un-crowded, with carpeting in some areas. It's capable of handling huge numbers of people, but today we've got plenty of room to roam. The indoor exhibits couldn't be more well protected or cared for, and are spaced for good photography. A visitor could spend an hour here, or a few days, depending on how much they wanted to see and learn. The average visitor, even one who likes trains, may not fully appreciate what they're seeing, but for me, here are legends that have thus far been only two-dimensional. Central Pacific's

C. P. Huntington and Governor Stanford , the Virginia & Truckee's Genoa, no longer images in a borrowed book from the library. It's easy to visualize Beebe & Clegg in their private car Gold Coast, dining in their tuxedos.

|

|

| Virginia & Truckee's 4-4-0 No. 12, named Genoa, was retired

by the railroad in 1908, but not scrapped. In 1938, it was sold to

the Eastern Presidents Conference for display at the 1939-40 Worlds

Fair in New York. Later displayed at the 1948-49 Chicago Railroad

Fair, it did not return west until 1948. Always a woodburner, it was

restored to its 1902 appearance when acquired by CSRM, and even

operated under its own steam briefly in the 1970s. |

|

|

|

Looking like new, but reportedly with a pitted boiler and broken cylinders, is former North Pacific Coast narrow gauge 4-4-0 No. 12, which once ran north from Sausalito into the mighty redwoods. Later, it ran on the Nevada Central. |

Some of the rolling stock can be removed rather easily if desired, but others, like the big SP Cab Forward, are likely there to stay, the building having been erected around them. A heavily-stripped and primered SP F7A, under restoration, is parked in the radial "roundhouse" section, and provides an effective lesson in restoring such a beast; it will involve a great many more hours of labor before the "black widow" paint job goes on. Nearby are Henry Sorenson's two narrow gauge saddletankers, both operable. One was found as an abandoned California derelict, the other from the Kiso Forest Railway in Japan. The latter was widened from 30-inch gauge to 36-inch, and I study the modifications.

|

|

|

This primered F7A is a former Southern Pacific unit, aptly demonstrating the amount of work needed to restore such a unit; it takes more than a mere paint job. |

|

|

|

These two narrow gauge saddletankers are privately owned and loaned to the Museum; both are in operable condition. |

Next door to the main Museum building is a replica facade of the Big Four Building, including the Huntington & Hopkins Hardware Co., from which the first shovels for the transcontinental railroad came. Behind the false fronts are the offices of the CSRM Foundation and the Museum's extensive library, which contains the photo collections of Gerald Best, Lucius Beebe, David Joslyn (a Southern Pacific employee who sometimes acted as its official photographer), Philip Hastings, and others, as well as many historic documents.

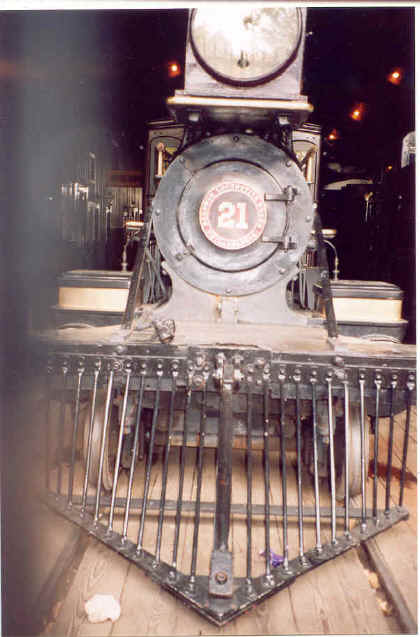

Closer to the river is the replica of the Central Pacific's first depot here, which on this day has the gates closed to its integral trainshed. The average visitor might just walk on, but I know the stories and

pause to reflect a bit. Behind the iron bars are some old favorites, including the "Death Valley Scotty" Santa Fe 2-6-2 and Virginia & Truckee's

J.W. Bowker 2-4-0 of 1875.

|

|

|

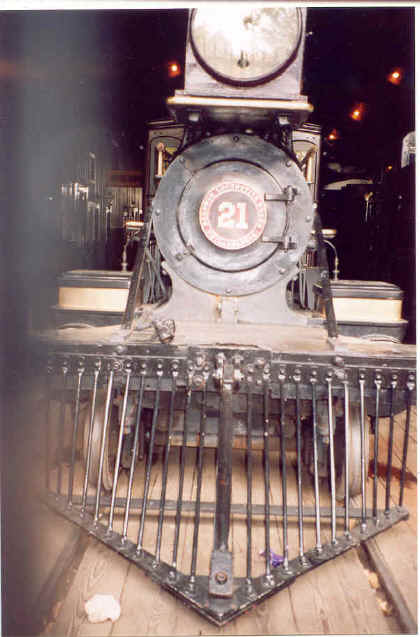

Peeking through its prison bars, V&T 2-4-0 No. 21 appeared in the classic movie Union Pacific and many other films. No longer operable, it's in good hands and under shelter. |

The "Scotty" engine appeared on television in the 1950s in an episode of Death Valley Days, chronicling the record setting Los Angeles-to Chicago race organized by Walter Scott as a publicity event. Originally a passenger engine with taller drivers, it was later rebuilt for local freight service, but as the lone survivor of the 14 locomotives that pulled the famous run, its legend lives on.

I recall not only the story, but also what a treat it was for this kid to see the program on TV, in an era devoid of video and the internet. The

Bowker, named after the V&T's Master Mechanic, had its name changed to

Mexico shortly after delivery due to Mr. Bowker's frequent inebriated state, which led to his dismissal. Bought as the Virginia City switch engine, it was sold to a nearby lumber company in 1896, and later saved by the

Pacific Coast Chapter, Railway & Locomotive Historical

Society, whose collection of old equipment formed the basis from which CSRM began. Cecil B. Demille borrowed it for his epic movie Union Pacific in 1939. Aside from a slightly different style of wooden cab, it looks almost like the day it rolled out of the Baldwin Locomotive Works in 1875 and retains its Knowles steam firefighting pump, an important asset to the frontier towns which burned down easily. As a

woodburner, it probably started some of the fires it helped put out.

|

|

|

Also in the replica trainshed is this former U.S. Army Transportation Corps 0-6-0T, which often pulls the Museum's Sacramento Southern excursion train. |

Also in the trainshed are the Museum's two operable steamers, Union Pacific 0-6-0 No. 4466 and Granite Rock 0-6-0T No. 10. The former was the last shop switcher at Cheyenne, finally ending its career working at Grand Island, Nebraska in 1958, where it sat until donation in 1973. Unusual for California, it burns coal. The 0-6-0T was a former U.S. Army Transportation Corps locomotive, a design sent overseas in droves during WWII. A few may even still be working at industries in China and the former Yugoslavia. The Museum has acquired an identical mate from Kentucky for parts, but I fail to spot it on this trip. No. 10 ended up at a quarry at Aromas, California; it has been partially

re-boilered by the Museum and like most far-west locomotives, burns oil. On the next track is SP E9 No. 6051, the last remaining SP E unit, adorned in its original Daylight colors. The unit runs, and has appeared at rail events all over California. The paint job mimics those found on its 4-8-4 predecessors.

Among the outside displays, there's a Santa Fe Warbonnet B unit, a Western Pacific F7A and an Amtrak F40, the latter of which I occasionally inspected when servicing the Vermonter train at St. Albans. At this time of year, the Museum's Sacramento Southern excursion trains operate only on weekends and the coaches sit silent today. An ex-Army SW8 is moving a car of lumber past the Museum, which actually has one revenue customer for freight.

|

|

|

To accommodate narrow gauge engines, three-rail track must turn into four-rail before reaching the turntable. |

There's some three-rail trackage, included to accommodate visiting narrow gauge engines for the two previous

Railfairs; the three rails turn into four before reaching the turntable, as they did at Alamosa, Colorado for so many years. CSRM's Railfairs have been about the only major public displays of railroading since the 1948-49 Chicago Railroad Fair. Sadly, few officials in the railroad industry today have an appreciation for its history, or of the value of public relations. Only the Union Pacific has made a steady effort at PR over the years and happily, they are a major player in the Museum's expansion efforts.

|

|

|

The only locomotive at the Museum that I've actually worked on is this Amtrak F40. I performed the daily trip inspection on it several times in St. Albans, Vermont. |

This expansion involves the former SP Sacramento Shops, of which the successor UP has leased two major buildings to the Museum, to become the Railroad Technology Museum. Paul knows I'm dying to see these, so we leave the polished floors of the main building behind, heading under I-5 and across the tracks, past piles of rubble. On the left is the former boiler shop, which Museum staff have recently begun using as a restoration facility. The corrugated tin siding still has the sign proclaiming it to be the Sacramento Locomotive Works. Inside is a multitude of machinery, some set up for use and some awaiting permanent installation. Most of the machines came from government surplus rather than railroad sources. SP pretty much gutted the place for scrap before moving out; the biggest assets they left behind are a relatively new drop table for changing wheels and traction motors, plus the overhead crane. This building also repaired tenders in steam days; a much taller section of the roof allowed boilers to be stood on end for riveting. The biggest project of many in the boiler shop is a newly-constructed transfer table, replacing the scrapped unit that once connected this building with the erecting shop across the way. Special welding fixtures had to be created for its replication. The original transfer table was an unusual design that ran in slots in its concrete pit, so simply replacing it with another table from somewhere else was not an option. The new table's completion will make moving equipment around a great deal easier. A pallet of new wheels for the table have been turned and await assembly; they're regular car wheels, but have been re-profiled with flat treads.

|

|

|

The re-created transfer table will once again connect the boiler and erecting shops. An unusual, home-built design, part of its carriage runs in slots in the concrete. |

At the far end of the boiler shop is a metal running repair shed, filled with the Santa Fe's historic diesel collection. Lots of rare birds here, including Fairbanks Morse, Alco and EMD units, all in their later blue and yellow paint scheme. Beyond that is the 100-foot turntable, across which sits a Santa Fe 2-10-4. There is little evidence of the former roundhouse, razed after the end of steam. The old floor, pits and foundation have been covered by a later application of concrete.

|

|

|

Stretching right over the 100-foot turntable, Santa Fe 2-10-4 No. 5021 has 74-inch drivers and could run at passenger train speeds. It was stored at Belen, New Mexico and later Albuquerque for several years before donation to

CSRM. |

|

|

|

No. 5021's counterpart for passenger service is 4-8-4 No. 2925. Santa Fe once evaluated it for rebuilding to operation, but dropped the project. |

The condition of the Santa Fe collection has been the subject of criticism by many. While not yet suitable for display, the big Texas type and 4-8-4 have had asbestos removed, are relatively stabilized and will receive work eventually. Personally, I think the Santa Fe collection belongs elsewhere, as Sacramento has enough to do already and the AT&SF never ran here. The railroad once proposed a company museum at its Albuquerque shops, which didn't materialize; what remains there is now proposed for redevelopment, but it appears to be more commercial than historic. The San Bernardino shop facility, complete save for a turntable until it was closed and razed in 1996, would have made another excellent museum, but the site now hosts an intermodal yard. The Redondo Junction roundhouse in Los Angeles could have been another suitable venue, but was torn down about a year ago, with no attempt to save it. The very last Santa Fe roundhouse, used for private storage, is still intact at Las Vegas, New Mexico, but thus far there have been no cries for its conversion to a museum.

|

|

|

America's most famous diesel face, thanks to Lionel and the movies, is the Santa Fe F7A, of which the Museum has the last extant example. |

|

|

|

Santa Fe's M-190 motorcar awaits restoration outside. It was re-engined with a 12-cylinder EMD 567 in 1949, and could pull four heavyweight passenger cars. |

|

|

|

Parked under a running repair shed are several historic diesels from the Santa Fe collection. |

Across the transfer table from the boiler shop is Sacramento's erecting and machine shop. The older portion of this building is where Master Mechanic

A.J. Stevens built his "monkey motion" 4-4-0s with their unique outside valve gear, and the one-of-a-kind El Gobernador 4-10-0, which proved too heavy for the track structure of its time. As engines grew, the building was doubled in size; SP built its last 4-8-2 here in 1930, with some 0-8-0s (using discarded 4-4-2 boilers) following in 1937. A few Sacramento-built engines survive even today. In the shop's last years,

hard-hatted workers did heavy upgrades on SD9s and GP9s, extending their service lives another 20 years. Today, the erecting shop houses a handful of locomotives and cars, a lot of stored parts, and a clan of feral cats who've taken up residence. There are more old favorites under tarps, including the last Northwestern Pacific ten-wheeler and Little Buttercup, a onetime saddletank 0-4-0 that spent most of its life as the shop switcher at Needles, California. In 1948, it was selected to represent the Santa Fe at the Chicago Railroad Fair, losing its ungainly water tank and gaining a tender from another departed engine. It too eventually became a movie star, being donated to CSRM in the 1980s.

|

|

|

Hiding under tarps in the erecting shop are the Santa Fe's Little Buttercup 0-4-0, and Northwestern Pacific 4-6-0 No. 112, the last extant NWP steam locomotive. |

|

|

|

Among numerous odd artifacts in the erecting shop is this 1940s Union Pacific bus, originally used in the Los Angeles area. |

Down the row is the disassembled carcass of SP 1771, a 2-6-0 I've known since age 6, when I first saw a picture of it in Railroad magazine. It was a Richard Steinheimer article on SP operations in California's scorching Imperial Valley. No. 1771 was fired up and hot in the evocative night shot, ready to go out and switch sugar beets. I still have the tattered magazine, bought in a Kansas drugstore, and I think about how long it's taken for the engine and me to meet in person. Escaping scrap, the Mogul was donated to Placerville, California for display in 1958 and was brought down to the Museum in 1985. Dismantling for repairs unfortunately showed it to have a pitted boiler and it now awaits either a new one or reassembly for static display. Ironically, Old Battler, a derelict Alco 0-4-0T that also appeared in the Steinheimer article was also saved and restored to operation. It visited the Sacramento Railfairs also, still trailing its ancient slope-back tender, and has since gone back to the Imperial Valley.

|

|

|

This stripped Mogul in the erecting shop is former SP No. 1771, a favorite of mine since childhood, when it appeared in a Richard Steinheimer article in the old Railroad magazine. |

|

|

|

These ancient, rusty fireboxes were dug up by remediation crews removing polluted soil around the shops. |

|

|

|

Not glamorous, but essential for heating old coaches, are these steam generators removed from SP diesels; few of these have been saved. |

Paul and I discuss how the shops will evolve into the Museum. The boiler shop will continue its restoration activities, with limited public access, but the final design of the erecting shop has not evolved yet. Personally, I vote for making it as authentic as possible, retaining as much "true grit" as practical, housing appropriate SP locomotives. Where an architect, more familiar with adaptive reuse retail projects, might specify a complete chemical washdown and sandblasting of old beams, I'd just fix the roof and sweep the floor, making as few changes to the historic fabric as possible. Railroad facilities, after all, were not shopping malls; workers toiled in grease, grime and soot. There has to be a balance between how things were and what the public will endure, but it's easy to go overboard with cleanup and modifications. Unlike the main Museum building, this is a genuine historic site, which calls, in my opinion, for a different type of interpretation.

|

|

|

Sacramento Locomotive Works painted on the old boiler shop is not an exaggeration; the Central Pacific and later Southern Pacific actually built new locomotives here into the 1930s. |

|

|

| Outside, among a large collection of passenger and freight cars

is this dieselized big hook, which formerly served the SP at nearby

Roseville, California. |

|

|

| The former coach shop and other buildings are not part of the

Museum's property; they will likely see development into

retail/commercial space. |

In all, there are eight major shop buildings left in the complex, including a car shop, blacksmith shop, a three-story toilet, a car shop machine annex, a paint shop and a planing mill. The fate of the others, still owned by the railroad, is presently unclear, as UP and the city debate over their future, but major changes will likely occur. It is probable that the buildings will survive, possibly as retail, office and entertainment venues. Future changes in the area include moving the mainline railroad tracks closer to the shop buildings, and a full restoration of Sacramento's classic depot. The depot, now host to many daily commuter trains, is busier than ever, but looks fenced-in and tired. It is quite similar to San Jose's Diridon station that I visited last year. I hope they do the same kind of job here that they did down there, simply sprucing it up, but not destroying its classic character. Sacramento's decorative vaulted ceiling is especially beautiful. The Museum, shops and depot areas will likely be connected by some sort of covered promenade. A major sports stadium may also enter the picture. The old Unit Shop (for repair of superheater units) that CSRM previously used as a restoration facility has been razed and that area is now covered with polluted soil being aerated. Just how the whole site will evolve is not fully clear yet. UP and the city recently agreed on a developer.

|

|

|

The Sacramento station will receive a major restoration; today, thanks to commuters, its serves more trains than at any time in its history. |

This Museum expansion succeeds a previous plan that I'm thankful never got past the drawing stage. The Museum of Railroad Technology, MORT for short, was to be another new building housing the remaining equipment. Critics, myself included, called it a "shopping mall with trains" and wondered why more effort wasn't being given to saving the historic SP shops, which were obviously outmoded and likely to be closed before long. At the time, SP was in dire financial straits and not able to donate them; fortunately, with the UP's takeover of the railroad, the buildings became available in time to be saved.

|

|

|

From the Museum's own website is this artists rendering and description of what the Railroad Technology Museum might look like, with some overtones of a festival marketplace. |

After our tour, we bade goodbye to Paul and retired to lunch in the Silver Palace Eating Stand (I recommend it) in the Old Sacramento station, which the Foundation now runs after losing its last operator. The next morning it was off to San Francisco, California's gold country, Yosemite and

Nevada.

~ to be continued ~

|